- Home

- YOUR FUTURE

- AI / Artificial Intelligence, Cybersecurity and Robotics

- Future of Marketing Keynotes

- Future of Retail / Food / Drink

- Future of Banking / FinTech / Fund Management

- Future of Insurance and Risk Management

- Mobile, Telco Keynote Speaker

- Global Economic Trends

- Future of Travel / Transport / Cars / Trucks / Aviation / Rail

- Future Hotels Leisure, Hospitality

- Future Healthcare Keynotes / Pharma Keynotes

- Future BioTech and MedTech

- Innovation Keynote Speaker

- Leadership, Strategy and Ethics

- Motivational Speaker for Change

- Future of Manufacturing 4.0, Manufacturing 5.0 keynote speaker

- Future Logistics / Supply Chain Risks

- Future Films, Music, TV, Radio, Print

- Future Green Tech / Sustainabilty

- Future Energy / Petrochemicals

- Future of Construction, Smart Cities

- Futurist Keynotes

- FUTURE EVENTS

- How Patrick Dixon will transform your event as a Futurist speaker

- How world-class Conference Speakers always change lives

- Keynote Speaker: 20 tests before booking ANY keynote speaker

- How to Deliver World Class Virtual Events and Keynotes

- 50 reasons for Patrick Dixon to give a Futurist Keynote at your event

- Futurist Keynote Speaker - what is a Futurist? How do they work?

- Keys to Accurate Forecasting - Futurist Keynote Speaker with 25 year track record

- Reserve / protect date for your event / keynote booking today

- Technical setup for Futurist Keynotes / Lectures / Your Event

- Dr Patrick Dixon MBE

- Futurist Books

- 18 books by Futurist P Dixon

- How AI Will Change Your Life

- The Future of Almost Everything

- SustainAgility - Green Tech

- Building a Better Business

- Futurewise - Futurist MegaTrends

- Genetic Revolution - BioTech

- The Truth about Westminster

- The Truth about Drugs

- The Truth about AIDS

- Island of Bolay - BioTech novel

- The Rising Price of Love

- Clients

- CONTACT for KEYNOTES

Patrick Dixon - Futurist Keynote Speaker "How AI Will Change Your Life" - BESTSELLER IN AIRPORTS FOR 12 MONTHS

29 Years Experience in Future Trends Forecasting >400 Global Clients - Every Industry and Region

How AI is transforming Pharma and health care. 10m lives a year will be saved. Keynote on health

The TRUTH about the FUTURE including AI - all major trends are VERY closely interlinked - AI keynote

How to use AI to stay ahead at work

Connect your brain into AI? Keynote speaker on AI and why emotion, passion and purpose really matter

THIS IS OUR FUTURE: 1bn children growing up fast, 85% in emerging markets. Futurist Keynote Speaker on global trends, advisor to over 400 of the world's largest corporations, often sharing platform with their CEOs at their most important global events

AI impact on pharma, medtech, biotech, health care innovation. Why AI will save 10m lives a year by 2035. Dr Patrick Dixon is a Physician and a Global Futurist Keynote Speaker, working with many of the world's largest health / AI companies

Most board debates about FUTURE are about TIMING, not events. Futurist Strategy Keynote speaker

Logistics Trends - thrive in chaos Seize opportunity with cash, agility and trust. Logistics Keynote

Future of Logistics - Logistics World Mexico City - keynote on logistics and supply chain management

Truth about AI and Sustainability - huge positive impact of AI on ESG UN goals, but energy consumed

AI will help a sustainable future - despite massive energy and water consumption. AI Keynote speaker

The TRUTH about AI. How AI will change your life - new AI book. BESTSELLER LIST AIRPORTS GLOBALLY - WH SMITHS FOR 12 MONTHs, beyond all the hype. Practical Guide by Futurist Keynote Speaker Patrick Dixon

How AI Will Change Your Life: author, AI keynote speaker Patrick Dixon, Heathrow Airport WH Smiths - has been in SMITHS BESTSELLER LIST FOR 12 MONTHs IN AIRPORTS AROUND WORLD

How AI will change your life - a Futurist's Guide to a Super-Smart World - Patrick Dixon - BESTSELLER 12 MONTHs. Global Keynote Speaker AI, Author 18 BOOKS, Europe's Leading Futurist, 28 year track record advising large multinationals. CALL +447768511390

How AI Will Change Your Life - A Futurist's Guide to a Super-Smart World - Patrick Dixon signs books and talks about key messages - future of AI, how AI will change us all, how to respond to AI in business, personal life, government. BESTSELLER BOOK

Future of Sales and Marketing in 2030: physical audience of 800 + 300 virtual at hybrid event. Digital marketing / AI, location marketing. How to create MAGIC in new marketing campaigns. Future of Marketing Keynote Speaker

TRUST is the most important thing you sell. Even more TRUE for every business because of AI. How to BUILD TRUST, win market share, retain contracts, gain customers. Future logistics and supply chain management. Futurist Keynote Speaker

Future of Artificial intelligence - discussion on AI opportunities and Artificial Intelligence threats. From AI predictions to Artificial Intelligence control of our world. What is the risk of AI destroying our world? Truth about Artificial Intelligence

How to make virtual keynotes more real and engaging - how I appeared as an "avatar" on stage when I broke my ankle and could not fly to give opening keynote on innovation in aviation for. ZAL event in Hamburg

"I'm doing a new book" - 60 seconds to make you smile. Most people care about making a difference, achieving great things, in a great team but are not interested in growth targets. Over 270,000 views of full leadership keynote for over 4000 executives

Deflation - the real risks to global economy and future of banking - ARCHIVE 2010 - very accurate forecastin. Futurist Keynote Speaker - global economy

Futurist Keynote Speaker: Posts, Slides, Videos - Banks, Banking, Insurance, Fund Management

Video recorded in April 2010 but the issues remained very relevant in 2013 (despite some warnings of inflation heading into 2014)

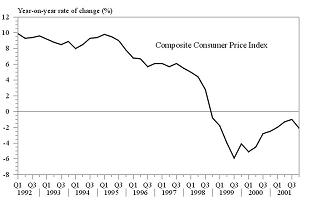

Hong Kong Composite Consumer Price Index - Source: HK government

Future of Banking: At the 2003 World Economic Forum meetings in Davos there was much talk about the possibilities of deflation: a real and growing threat to a number of economies, despite the fact that most governments have been obsessed with reducing inflation. Indeed entire government economic policy has often been focussed on just one main factor: killing inflation. Why?

Soaring inflation rates have been blamed for many national crises and even for causing wars. Time and again we have seen countries with out-of-control cost of living rises: strikes, industrial action and high wage demands all feeding into higher production costs, encouraging a spiral of further upward pressures on consumer prices. Inflation is often blamed for destroying the value of savings, and making people poor. But collapsing prices also creates a crisis - as we see in cycles of boom, bustle and bust.

Need a world-class keynote speaker on the global economy or banking? Phone Patrick Dixon now or email.

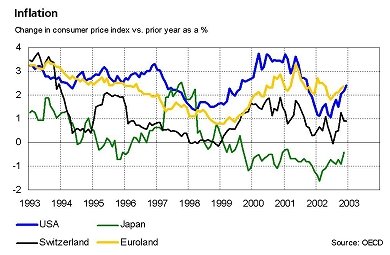

The US was deflating in 40% of goods and services

But the reality in 2002 was deflation across many industry sectors. Take the US economy. Prices for 40 percent of all the goods and services in the Labor Department's consumer price index (CPI) showed year-over-year declines in September 2002, according to research by Merrill Lynch's chief Canadian economist David Rosenberg. Corporations in the deflating sectors below form 25% of the stocks in Standard and Poor's 500 index.

Some think governments are being too slow to recognise the great dangers of low inflation, where a single economic blow can push an entire nation over the edge into deflation, with falling cash values of every asset and every investment.

Deflation means a complete mental rethink and is beyond the understanding of most people today who were raised in inflationary times. The real question is an emotional one: how will ordinary people behave if they think prices are going to fall year on year for more than a very short period?

And how will investors in the market behave? As we saw in Japan (1990s), if they start pricing in an expectation of deflation across most sectors, rather than just 40% in some sectors, it will have a significant effect on valuations and reduce appetite even more for buying stocks.

Consumers often rely on inflation to help them repay debts - particularly house loans. Inflation of 5% means a mortgage is only half what it was in real terms in 15 years.

What happens in deflation?

When prices fall, the value of cash rises. Anyone with money has an advantage and those with debts lose. If I have a mortgage of $250,000 this year, and deflation runs at 5% a year, it means in real terms my loan will double in size over 15 years. Most worryingly, in deflation, my loan (which was only 70% of the value of my home) will become so huge that even if I sell my home, I will be left with large debts.

We have all seen deflation before in one key area: computers and digital technology where deflation has been eating away at price levels for three decades or more. But this is different. It is one thing to write off an investment in a computer system over three years, but another to find that one of your greatest assets, your own home, is worth only a small fraction of what it was twenty years ago, and that prices of every other asset you own are also expected to go on falling.

Of course if you have cash in hand, the temptation is to spend nothing, and invest in nothing. What is the point of buying when you know that in six months time the chances are you could buy more? So money gets left as cash under the bed, or in a bank account (if you are prepared to risk the bank going bust because so many loans were secured against assets, now worth almost nothing). Spending falls, feeding a further frenzy of price cutting, downward pressure on salaries, bonus cutting, and so on. But it is easier to pay people less and get away with it when they know they need less to live on this year than last year.

Interest rates fall to zero, because no one in their right minds wants to borrow large amounts of an asset (cash) which is going to inflate with time. Indeed the only asset for ordinary men and women that grows in value in a deflationary economy is cash, and cash is what you find they hang on to. Just look at Japan which has experienced deflation for years with terrible consequences.

How serious is the risk of deflation hitting other economies?

What happens when interest rates fall to zero

The main tool that governments use to control inflation is interest rates, but this tool can lose its power if rates are already so low that there is hardly any room left to cut further before the cost of borrowing falls to zero. Another terrorist shock, a war in Iraq that goes badly wrong, or some other national calamity... it is not hard to imagine a scenario where further rate cuts become necessary.

Think about it from the ordinary man or woman in the street's point of view. If interest rates are zero, I can go out and get a huge loan and it costs me nothing at all. Of course the loan must one day be repaid, but when? The bank soon realises I am over extended and cannot repay, but is in no hurry because the loan repayments will be worth more to them in the future, if they give me longer to find the money. They are not losing a penny in interest because the interest rate is zero. In fact every day the bank waits, the more they make, because the price of money is rising as the price of everything else falls - that is the reality of deflation.

Old economics relied on inflation running at a safe modest level - not too high and not too low. It taught us that raising the cost of borrowing also raises the returns to savers, and sucks money out of the economy so less is around to be spent by consumers, goods hang around before being sold and market prices are constrained. Lowering interest rates encourages people to spend without worrying, more cash chases goods for sale, prices rise.

Unfortunately there are a number of drivers of deflation, so it will be easy for governments to find rates lower turn out lower than they expected. That's why banks try to keep a margin for error and will take radical steps to prevent inflation falling from - say - an absolute minimum of 2.5% or even 3% a year.

Deflation Drivers

1. Globalization: every time a job moves from a high income country to a low income country, the price of production falls, and the potential for price cutting increases, while maintaining profits and market share. We are currently witnessing rapid and accelerating changes in industry and services. Even less developed countries like Mexico are finding large chunks of their manufacturing capacity moving to places such as China. India is taking a significant share of software development, with entire teams being made redundant in the UK and the US, replaced by teams twice the size at a fraction of the cost in places like Hyderabad and Bangalore. And as prices rise in places like coastal China, jobs will shift to other less developed regions.

2. Technology innovation: every time a new production process is developed, using less people and less resources, prices fall. In the past, technology purchases formed only a small part of our lives, but the techno-economy continues to grow dramatically, despite the hype and gloom of investors. And the indirect spin-offs are becoming greater every day. Take for example food technology and processing, where new automated packaging and distribution systems have contributed to falling food prices for over a decade, or new farming methods with increased yields, or the impact of online business to business relationships and just-in-time delivery systems.

3. Economic cycles and global shocks. Every economy goes through ups and downs and events outside any government's control also have impact. Take for example major terror attacks or turmoils in the Middle East affecting oil prices, which have recently fluctuated widely and may continue to do so. When oil prices rise, there is inflationary pressure. Governments respond by factoring this into decisions to raise interest rates and inflation falls towards a base level. But if that minimum is too low, what happens if there is another major downwards correction and for a while oil prices fall very significantly? The answer is an added risk of undershooting and causing deflation.

Acting to prevent further deflation

So then, as we have seen, sectors in many economies are already deflating. What can governments do of they are worried about deflation, or to correct national deflation once it starts?

Firstly they can cut interest rates more aggressively while they are still able.

Secondly they can suspend or revoke tax rises for a limited period. Thirdly they can increase expenditure. Both these options of course affect government debt and are sustainable only in the short term without profound consequencies.

In summary then, both inflation and deflation pressures can worry governments, with potential risks to stability in countries where inflation has been allowed to fall too low. Governments should be expected to act from time to time, aiming to maintain around 2.5% to 3.0% inflation throughout economic cycles, giving room for adjustments and economic shocks in both directions.

Need a world-class keynote speaker on the global economy or banking? Phone Patrick Dixon now or email.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|

Newer news items:

- Future of Fund Management and Banking - Keynote Speaker

- Future of Stock Exchanges and Investment why local trading communities survive. Financial Services Keynote Speaker

- Future of Fund Management: banks, pensions, trust, banking crisis and investment performance

- Listing on Stock Exchange blessing or curse? Future investment and banking trends

- Mobile payments threaten retail banks / credit cards

- Spam and fraud threat to future of banking. FUTURIST Q&A Patrick Dixon

- Zopa Loans - Boom in Peer to Peer Lending - Future of Banking Keynote Speaker

- When will banking profits recover? Keynote speaker on Future of Banking

- Future of Banking, Bank trends, AI, FinTech, Fund Management, Cryptocurrencies

- How to lose $ millions - video on risk. Future of Banking Keynote Speaker

- Future of Banking: How to lose millions - dangers from "unique" business offers. Business risks and scandals. Lessons from collapse of Icelandic Banks

- Future of Banking - Credit Crunch - Banking Trends - Futurist Keynote Speaker

- Credit Crunch and Sub-Prime Crisis - 2008 Video on Future of Banking - turned out to be very perceptive. Future of Banking Keynote Speaker

- What next in the Sub-Prime Crisis? - Video on Future of Banking / Economy

- Future of Banking: New Technology impact on Corporate Banking - 25 year track record of accurate forecasting of banking megatrends by Futurist Keynote Speaker Patrick Dixon

Older news items:

- Future of Banking - Web TV - ARCHIVE 1997

- Future of Banking - EU Online Banking - ARCHIVE 1997

- Future of Banking: Online Banking outside US / EU - ARCHIVE 2007

- Future of Banking - US Online Banking - ARCHIVE 1997

- Future of Banking: Online Banking Competitors - ARCHIVE 1997

- Future of Banking: Online Threat to Banks - ARCHIVE 1997

- Future of Banking: Growing demand for cyberbanking in EU

- Future of Banking: Digital Meltdown of Financial Services - Video - Archive 1998

- Future of Banking: Merger fever in EU - ARCHIVE 1998

- Future of Banking - ARCHIVE 2002 - Futurist banking keynote speaker

- Web TV - future of banking and financial services

- Future of Investment Banking - End of "Old" Stock Exchanges

- The Death of Stock Exchanges - feature on Future of Stock Exchanges and Trading Platforms for Time Magazine - by Futurist Keynote Speaker Patrick Dixon

- Future of Banking and Financial Services

Thanks for promoting with Facebook LIKE or Tweet. Really interested to read your views. Post below.

Futurist Keynote Speaker - New

- THIS IS YOUR FUTURE: Greatest Megatrend of All is 1 billion children alive today, 85% in emerging markets. What they do, how they live, their hopes and dreams will shape the next 50 years. And 1 billion adults will migrate to cities in the next 30 years

- AI impact on MedTech, BioTech, Health Care innovation. Why AI could drive $50bn a year sales. Dr Patrick Dixon is a Futurist Keynote Speaker, worked with many of world's largest BioTech and MedTech companies. BESTSELLER AI BOOK

- TRUTH about US trade War - what next? Why markets and voters more powerful than any US President. How chaos will resolve and likely end result. Patrick Dixon is global keynote speaker on economy and geopolitics

- Truth about US trade chaos. How Tarrifs will settle and why. Power of global markets and megatrends greater than any President. Comment after keynote at Logistics World in Mexico. Futurist Keynote Speaker

- How US trade tariff chaos will settle and why - impact on US economy, Mexico, Canada, EU and other regions. Comment after Mexico Keynote at Logistics World. Futurist Keynote Speaker

- Beyond Chaos - how to survive and thrive. What next for global trade, tariffs, Russian war, other geopolitical risks and the global economy. Futurist Keynote Speaker

- How to give world-class presentations. Keys to great keynotes. How to communicate better and win audiences over. Expert coaching for CEOs, Executives, keynote speakers – via Zoom or face to face. Patrick Dixon is one of the world's best keynote speakers

- Future of the Auto Industry: Why Our World Needs Low Cost Chinese e-vehicles. Impact of China electric cars on US and EU auto industry. Sustainability and GreenTech innovation keynote speaker

- Daily Telegraph:"If you need to acquire instant AI mastery in time for your next board meeting, Dixon’s your man. Over two dozen chapters. Business types will enjoy Dixon's meticulous lists and his willingness to argue both sides." BUY AI BOOK NOW

- Interview: How AI Will Change Your Life - BESTSELLER 12 MONTHS airports globally. Bk author Patrick Dixon, keynote speaker on AI, in conversation with Alison Jones, Extraordinary Business Book Club. Looking for a keynote speaker on AI? BOOK AI Keynote NOW

- Impact of AI on $10tn PA food and beverage sales (F&B), fast moving consumer goods (FMCG). Why trust and emotion matter in an AI-influenced retail world. Extract Ch16 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - Patrick Dixon Futurist Keynote Speaker

- AI in Government. Impact of AI on state departments, AI efficiency, AI cost-saving. AI policy decisions and global regulation of AI. Extract Ch26 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, keynote speaker on insurance and AI

- AI warfare: AI in future conflicts. Battlefield AI, impact of AI on defence, military budgets, AI hybrid weapons, armed forces strategy. Extract Ch25 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, keynote speaker on Defence and AI

- AI will create HUGE new cybersecurity risks, hijacked by criminals and rogue states. Paralysis of companies, hospitals, governments. Extract Ch23 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - Patrick Dixon, keynote speaker - cybersecurity and AI

- AI for Insurance: how AI will impact AI in underwriting, quotes, re-insurance. AI will improve claims handling, AI reducing fraud. Extract Ch22 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, keynote speaker on insurance and AI

- How AI will impact banks: AI will save bank core costs, deliver better banking services, but AI will also create huge new banking risks. Extract Ch22 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, keynote speaker on banking and AI

- AI Investing, AI in Fund Management, Pension Funds, AI trading in Stock Markets and Global Financial Services AI, Banking AI. Extract Ch21 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, keynote speaker on Fund Management AI

- How AI will double digital energy consumption globally in 10 years. AI will have huge impact on energy, environment, sustainability. Extract Ch20 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, keynote speaker on sustainable AI

- AI in Construction - future Impact of AI on built environment. Buildings design, architecture, site development, AI in smart cities. Extract Ch19 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, keynote speaker on AI in construction

- Manufacturing AI. How AI will transform factories and manufacturing, including AI logistics and AI-driven supply chain management. Extract Ch18 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, keynote speaker on AI in manufacturing

- AI impact on travel, tourism AI, transport AI, auto industry AI, aviation AI, airlines. How AI will change the travel experience.Extract Ch14 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, keynote speaker on AI for travel industry

- Future of retail AI: impact on retail sales, retail marketing, customer choice, AI predicts demand, AI warehouse, AI supply chains.Extract Ch13 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, keynote speaker on AI retail trends

- Future Marketing: Impact of AI on Marketing - how AI will transform marketing, AI trends in advertising. Extract from Ch12 BESTSELLING BOOK AIRPORTS IN GLOBALLY: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, keynote speaker on AI marketing

- Impact of AI on search engines, what AI means for news sites, AI in social media, AI in publishing and AI art copyright. Extract Ch11 - BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, AI keynote speaker

- Future of Music Industry: AI impact on music, musicians, record labels, AI composing, AI lyrics, AI copyright violations. AI for song-writers, singers, album producers.Extract Ch10 BESTSELLER bk How AI will change your life - Patrick Dixon Keynote Speaker

- Future Film, TV, Media, video games - impact of AI on film-making, AI movies, AI in studios, post-production AI, computer games.Extract Ch10 BESTSELLER book How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, AI keynote speaker on film industry, TV and media

- Impact of AI on software development, programming, high level coding, AI system design, and AI strategy. Extract Ch9 BESTSELLER new book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, AI keynote speaker on software and IT strategy / design

- Impact of AI on adult education.Teaching entire nations how to tell what is true v fake news, AI scams or false consipiracy theories. Extract Ch9 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, AI keynote speaker on education

- Future of Education - Impact of AI on Teaching, Schools and Colleges. Why AI will force radical changes in teaching curriculum and methods. Extract Ch7 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, AI keynote speaker on education

- Impact of AI on Pharma, Drug Discovery, Drug Development and Clinical Trials.10m lives Will Be Saved A Year Globally Because Of AI In Pharma and Health. Extract Ch6 BESTSELLER BOOK How AI Will Change Your Life. Dr Patrick Dixon, Pharma AI Keynote Speaker

- How health care, hospitals and community care will be impacted by AI. 10 million lives will be saved a year globally because of AI in health. Extract Ch5 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - Dr Patrick Dixon, health and AI keynote speaker

- How will AI impact office workers, teams and working from home (WFH)? Lessons for every team leader, manager and leader on AI impact at work. Extract from Chapter 4 How AI will Change Your Life by Patrick Dixon, AI keynote speaker. BESTSELLER LIST 11mths

- Why AI will result in MORE JOBS. Myth of global job destruction from AI due to net job creation. How will AI impact the workplace and work itself? Extract Ch3 BESTSELLER book: How AI will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, AI keynote speaker

- Super-Smart AI and a Reality Check. How Super-smart AI will become conscious, posing all kinds of new Super AI / AGI risks to future humanity. Extract Chapter 2 BESTSELLER Book: How AI Will Change Your Life - by Patrick Dixon, AI keynote speaker

- The TRUTH about AI / Artificial Intelligence. What is REALLY happening and why this matters now for your personal life, job and wider world. Extract Ch1 book: How AI will Change Your Life by Patrick Dixon, AI keynote speaker. BESTSELLER LIST 11 MTHS

- Impact of AI on Health Care and Pharma – Artificial intelligence keynote outline for Pharma companies and health care organisations. How will AI drive future AI innovation in health and Pharma?

- How AI will change your life - BESTSELLER book, out NOW A Futurist's guide to a super-smart world. 28 chapters on impact of AI in industry, government, company, personal lives. Patrick Dixon is a world leading keynote speaker on AI. CALL +44 7768511390

- Risk of Russia war with NATO. Russia's past is key to it's military future. War and Russian economy, Russian foreign policy and political aspirations, future relationship between Russia, China, EU, NATO and America - geopolitical risks keynote speaker

- Over 2 million have watched my Green Energy Webinar! "Next 20 years will determine future of humanity": predictions for 40 years. Massive scaling green tech. Race for solar, wind v coal, oil, gas. Climate emergency. Futurist Keynote for Enel Green Power

- How AI / Artificial Intelligence will transform every industry and nation - banking, insurance, retail, manufacturing, travel and leisure, health care, marketing and so on - What AI thinks about the future of AI? Threats from AI? Keynote speaker

- The Future of AI keynote speaker. Will AI destroy the world? Truth about AI risks and benefits. (Some of this AI post written by AI ChatGPT - does it matter?). Impact of AI on security, privacy AI, defence AI, government AI - keynote speaker

- Future of Rail in 2030: trends in rail passengers, rail freight, railway innovation. High speed rail, impact on aviation. Rail logistics and supply chain management. AI impact, Zero carbon hydrogen powered railway locomotives - Rail Trends Keynote

- Future of the Auto Industry 2040. Trends impacting the auto industry, car manufacturers, truck factories. Auto industry innovation, autonomous vehicles, flying cars, vehicle ownership, car insurance AI / Artificial Intelligence.Futurist Keynote for Belron

- Future of Aviation: Carbon Zero Planes. New fuels such as hydrogen, smaller short distance battery powered vertical take-off vehicles. Why Sustainable Aviation Fuel is not the answer to global warming. 100s of innovations such as AI will impact aviation

- THE TRUTH ABOUT FUTURE MASS MIGRATION - a people movement with greater force than any military superpower. As I predicted in "Futurewise" (1998-2005), large scale migration is now unstoppable, able to break governments, yet many nations NEED migration

Popular - Futurist Speaker

- Futurist Keynote Speaker Website - Sorry - something has gone wrong! We will check it out...

- Futurist Speakers: How keynote by Patrick Dixon will transform your event. Visionary, high impact, high energy, entertaining Futurist keynotes on future trends. Keynotes on AI, tech, health, marketing, manufacturing etc. 370,000 reads. CALL +44 7768511390

- Conference Speakers: How Great Conference Speakers Change Lives. 10 tests BEFORE booking top conference speakers. Keys to world-class events. Secrets of ALL best keynote speakers. Who are best keynote speakers in world? 327,000 reads. CALL +44 7768511390

- Future of Marketing 2030 - Marketing Videos, key marketing trends and impact of AI on marketing campaigns. Conference Keynote Speaker on Marketing - 234,000 have read this post. Marketing Keynote Speaker: CALL NOW +44 7768 511390

- The Future of Outsourcing in world beyond AI - Impact on Jobs - Futurist keynote speaker on opportunities and risks from outsourcing / offshoring. Why many jobs coming home (reshoring - shorter supply chains). AI and new risk, higher agility. 200000 views

- The Truth About Drugs - free book by Dr Patrick Dixon - research on drug dependency, addiction and impact on society of illegal drugs

- Future of Stem Cell Research - Creating New organs and repairing old ones. Trends in Regenerative Medicine, anti-ageing research, AI. Future pharma, clinical trials, medical research, heath care trends, and biotech innovation.Health care keynote speaker

- Future of the European Union - Enlarged or Broken? What direction for the EU over the next two decades? Geopolitics keynote speaker

- The Truth About Westminster

- 10 trends that will really DOMINATE our future - all predictable, changing slowly with huge future impact - based on book The Future of Almost Everything by world-renowned Futurist keynote speaker. Over 100,000 views of this post. Discover your future!

- The Truth about AIDS

- Future of the Automotive Industry (Auto Trends) - e-cars, lorries, trucks and road transport trends, reducing CO2 emissions, e-cars, eVTOL flying vehicles, hydrogen, autonomous AI drivers, auto industry impact from AI. Futurist keynote speaker

- Marketing to Older Consumers - 1.4 billion over 60 year old consumers by 2030. Future of Marketing Keynote Speaker. Ageing customers, strategies to target older consumers and other marketing trends. Why many companies fail in marketing to older people

- Future of Aviation Industry. Rapid bounce back after COVID AS I PREDICTED. Most airlines and airports were unprepared for recovery. Aviation keynote Speaker. Fuel efficiency, reducing CO2, hydrogen fuel, AI, zero carbon, flying taxis (eVTOL)

- Sustainagility: innovation will help save world. Sustainable business keynote speaker

- China as world's dominant superpower - Impact on America, Russia and EU. Futurist keynote speaker on global economy, emerging markets, geopolitics and major market trends

- Patrick Dixon Futurist Keynote Speaker - ranked one of top 20 most influential business thinkers, Chairman Global Change Ltd, Author 18 Futurist books. Call now to discuss a Transformational Futurist Keynote for Your Event: +44 7768 511390

- Web Traffic: Up to 2.9 million pages a month - Future Trends website of Patrick Dixon, Futurist Keynote Speaker

- Futurist Keynote Speakers. 20 secrets of world's best keynote speakers. How to select great keynote speakers for your events. Secrets of all top keynote speakers. Change how people see, think, feel and behave. Who are the best? CALL +44 77678 511390

- Total media audience >450 million on TV, Radio, Press Coverage of Patrick Dixon, Futurist Keynote Speaker - Call Patrick Dixon NOW for media interviews (or for event keynotes) on +44 7768 511390.